Pathogenesis

As one of the most severe complications of dermal filler, it is understandably something tht is rightfully feared among all clinicians. Cells need oxygen to function and stay healthy, necrosis is reduced or loss of oxygen to these cells for the demand needed, dysfunction and cell death ultimately can follow. Infection risk and scaring is possible once this has happened, in the context of being related to an aesthetics procedure this potentially catastrophic to your patient. Emphasis must be placed on how it occurs and its prevention, diagnosis, treatment and risk reduction.

Let’s look first at the pathogenesis of necrosis.

This understanding will help you effectively judge and diagnose a potential reduction in oxygen, to the required cells rapidly and at different points throughout the procedure.

Cells become distressed when the oxygen supply is not sufficient for demand, hence impending necrosis. This is fundamentally caused by dermal filler in facial aesthetics treatments.

There are several mechanisms in which this can happen:

BLOCKED ARTERY

- Complete occlusion where local blood supply cannot travel through its pathway effectively, no other blood supply available to nearby tissue

EMBOLUS

- This travels down the artery but into small vessels causing distal areas of necrosis

PRESURRE ON AN ARTERY

- No proven cases, but theoretically possible from reduced blood flow and swelling or dermal filler placement

PRESSURE ON THE CAPILLARIES

- Continuous pressure on the capillary bed reducing blood flow, similar to ulcer or pressure sore

VENOUS OCCLUSION

- Theoretically possible, if venous exit is prohibited then inflow of fresh blood may also be affected, risking blood supply options and delivery of oxygen in the area. Can happen most commonly in the eye area, although there should generally be collateral supply in areas of tissues treated for aesthetics

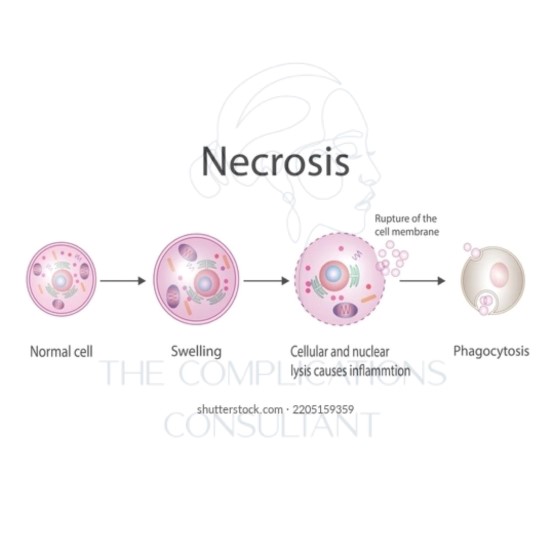

- On a cellular level

Necrosis is a form of cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue by autolysis. Necrosis is caused by factors external to the cell or tissue, such as infection, or trauma which result in the unregulated digestion of cell components. In contrast, apoptosis is a naturally occurring programmed and targeted cause of cellular death. While apoptosis often provides beneficial effects to the organism, necrosis is almost always detrimental and can be fatal.

Cellular death due to necrosis does not follow the apoptotic signal transduction pathway, but rather various receptors are activated and result in the loss of cell membrane integrity and an uncontrolled release of products of cell death into the extracellular space. This initiates in the surrounding tissue an inflammatory response, which attracts leukocytes and nearby phagocytes which eliminate the dead cells by phagocytosis. However, microbial damaging substances released by leukocytes would create collateral damage to surrounding tissues. This excess collateral damage inhibits the healing process. Thus, untreated necrosis results in a build-up of decomposing dead tissue and cell debris at or near the site of the cell death. A classic example is gangrene. For this reason, it is often necessary to remove necrotic tissue surgically, a procedure known as debridement.

Pathways

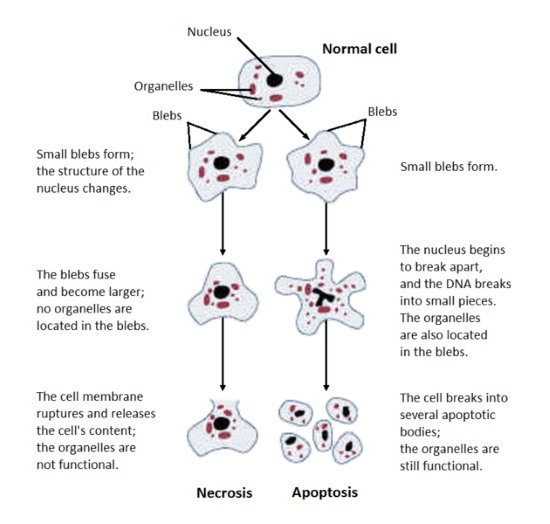

Until recently, necrosis was thought to be an unregulated process. However, there are two broad pathways in which necrosis may occur in an organism.

The first of these two pathways initially involves oncosis, where swelling of the cells occurs. Affected cells then proceed to blebbing, and this is followed by pyknosis, in which nuclear shrinkage transpires. In the final step of this pathway cell nuclei are dissolved into the cytoplasm, which is referred to as karyolysis.

The second pathway is a secondary form of necrosis that is shown to occur after apoptosis and budding. In these cellular changes of necrosis, the nucleus breaks into fragments (known as karyorrhexis)

The nucleus changes in necrosis and characteristics of this change are determined by the manner in which its DNA breaks down:

- Karyolysis: thechromatin of the nucleus fades due to the loss of the DNA by degradation.[6]

- Karyorrhexis: the shrunken nucleus fragments to complete dispersal.

- Pyknosis: the nucleus shrinks, and the chromatin condenses.

Other typical cellular changes in necrosis include:

- Cytoplasmic hypereosinophiliaon samples with H&E stain. It is seen as a darker stain of the cytoplasm.

- Thecell membrane appears discontinuous when viewed with an electron microscope. This discontinuous membrane is caused by cell blebbing and the loss of microvilli.

On a larger histologic scale, pseudopalisades (false palisades) are hypercellular zones that typically surrounds necrotic tissue. Pseudopalisading necrosis indicates an aggressive tumour.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necrosis

In summary

The ultimate risk factor for impending necrosis is lack of bloody supply and in turn lack of oxygen to cells that desperately require it to survive, when this is mitigated it results in uncontrolled cell death. Surrounding tissues as collateral are also ultimately affected.